Cannibalism and care in poison frogs

Patricia Jones

An Allobates femoralis carrying tadpoles on its back. Photo by Seabird McKeon.

It doesn't get much cooler than male parental care in poison dart frogs. This week's paper is in Scientific Reports, lead authored by Eva Ringler at the University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna, Austria. Allobates femoralis is distributed across the Amazon basin of South America. Paternal care is widespread (and thought to be ancestral) in the poison frogs. Males defend territories in the rainforest where females come to mate with them, and lay their eggs. A female will lay her clutch of eggs surrounded by jelly in the leaf litter on the forest floor. The eggs will develop for three weeks at which point the male will move the tadpoles to water sources. Males move tadpoles on their backs to little pools made by the leaves of plants such as bromeliads. Particularly relevant to this study is that males will even move tadpoles from clutches that are not their own, but were placed inside their territory.

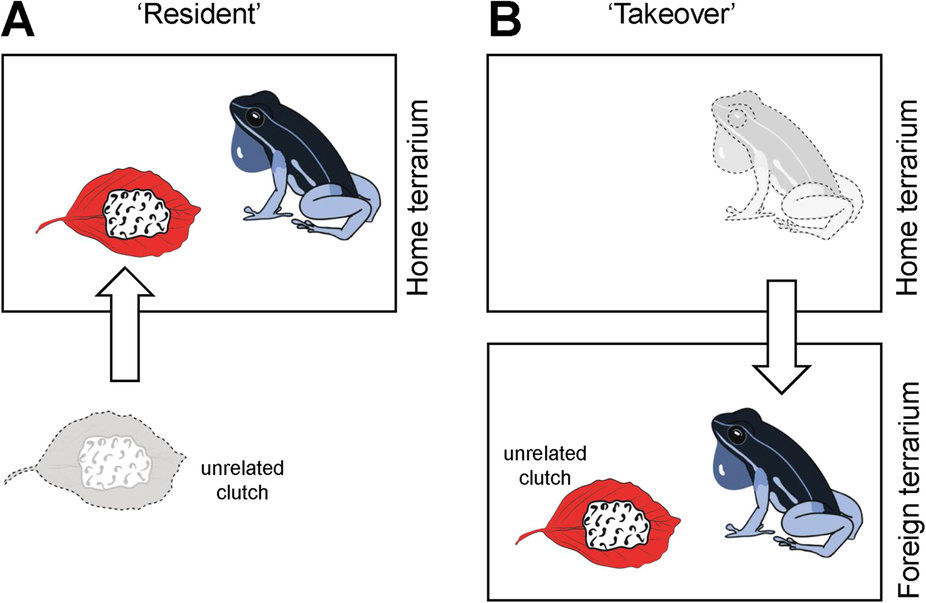

This study examined how male A. femoralis respond to the presence of unrelated clutches in their own territory, in comparison to males that are moved to a new territory (representing a territory "takeover"). The design was really simple and detailed in the picture below.

From: http://www.nature.com/articles/srep43544#s1

In the 'resident' treatment (A) males were removed from their home terrarium, an unrelated clutch was placed in their terrarium, and then they were returned. In the 'takeover' treatment (B) males were removed from their home terrarium and placed in a new terrarium with an unrelated clutch of eggs. So in both cases males experienced being captured and were given an unrelated egg clutch. They then recorded what males did with those eggs. Males in the 'takeoever' treatment were more likely to eat the eggs than males in the 'resident' treatment, and males in the 'resident' treatment were more likely to transport the tadpoles. The authors propose that males follow a simple strategy that allows them to maximize their fitness while minimizing energetic and cognitive costs. Clutches in their own territory are most likely their own, so they should care for them. Clutches in a new territory are certainly not their own, so they should eat them. Given that males defend their territories from invading males and only mate with females on their territories, they may not experience selection to be able to identify their own eggs from those of other males. It would be interesting to see if this type of territoriality trades off with offspring recognition in other systems.